INTRODUZIONE

Chinese in america

Sit back for a moment and imagine biting into a warm, savory egg roll. Or a juicy pork dumpling. Or for that matter, a spicy morsel of General Tso’s Chicken (page 70). Although the flavors vary from food to food, chances are we’re all imagining the same feeling: satisfaction.

Chinese takeout is in many ways an all-American cuisine. Many of us grew up eating as much Chinese food as we did hamburgers and hot dogs. It’s comfort food that has played a supporting role on many occasions, from potlucks to poker nights, from late-night study sessions to crosscountry road trips. Whetheryou’re in Brooklyn, Bozeman, or Biloxi, Chinese restaurants are ubiquitous. If you live in an urban area, chances are your kitchen drawers are filled to the brim with takeout menus, soy sauce packets, and disposable chopsticks.

American-style Chinese food predates the arrival of most regional Chinese cuisines that we now enjoy, including Sichuan, Hunan, and Fujianese. The first Chinese restaurants in the United States were opened in California in the late 1840s and 1850s, during the gold rush, by Cantonese immigrants who, due to prejudice, had a hard time finding work on the railroads. Most cooks taught themselves, re-creating foods from home with the ingredients they found in this strange new world. Restaurants in the mining towns catered to both Chinese and non-Chinese laborers; the food was cheap and came in hefty portions. In San Francisco more upscale restaurants drew urban sophisticates who were curious about the “exotic” dishes and eager to report back to their friends. When the Chinese and non-Chinese railroad workers began migrating east, the restaurants followed and flourished, especially in cities.

By the early twentieth century, popular Chinese dishes had become part of the cultural vernacular. Artist Edward Hopper produced a painting in 1929 that he titled Chop Suey, in which two women idle in a Chinese eatery over a pot of tea. In his novel Main Street, Sinclair Lewis describes how his city girl main character tries to introduce chow mein and other Chinese foods to her suburban neighbors in 1920s Minnesota. And the poet Carl Sandburg mentions egg foo young in his 1936 epic poem “The People, Yes.” (More recently, episodes of popular shows from Seinfeld to Sexandthe City have depicted Chinese restaurants and Chinese takeout as being ingrained in the lives of their characters.)

At midcentury, Chinese restaurants had become fashionable hangouts for young urbanites. At the Cotton Club in New York, you could order chow mein or fried rice along with your gin fizz. In California, tiki restaurants, spearheaded by the Trader Vic’s chain and Don the Beachcomber, created an entire dining experience around pupu platters of egg rolls, barbecued ribs, and wontons, with mai tais and Singapore slings to wash down all the food. In Manhattan in the 1970s, the concept of Chinese food delivery exploded in popularity. Soon, Chinese restaurants and the idea of takeout spread to the suburbs and small towns and became entrenched in the daily lives of millions of Americans.

Today there are more than forty thousand Chinese restaurants in the United States, and more are opening every day. Some have even made their versions of Chinese dishes into popular local specialties: You can order up kalua pork-steamed buns in Hawaii, chow mein sandwiches in Rhode Island, or soy vinegar crayfish in Louisiana. What began in this country as exotic has become thoroughly American.

American-Chinese food is a natural by-product of Chinese immigration, but it can be just as good as food eaten in mainland China. I avoid using the word “authentic” whenever possible, because all cuisines have evolved from somewhere, whether it be Cajun food, Italian food (tomato sauce was nonexistent in Italy until the late 1600s), American-Chinese food, or even Chinese food in China. Food almost always changes, and needs to change, across provinces, countries, and continents, adapting along the way to use local ingredients and to suit local tastes. If a chef needs to alter a dish, it’s not a travesty as long as he or she does it well and with care. Without cross-cultural fusion of cuisines, we wouldn’t have bagels with lox, deep-dish pizza, hamburgers, baked ziti, jambalaya, and many other iconic foods in America. Likewise, American-Chinese classics, such as chow mein and Shrimp with Lobster Sauce (page no), are also products of the American story, and delicious if cooked with care.

My own American story involved Chinese food that came in many different forms. When I was five, my family emigrated from China to Puerto Rico, where my parents worked at a Chinese-Latin restaurant that served entrées such as lo mein with a side of plantains. Later, when we moved to suburban Massachusetts, they helped my extended family run a Polynesian-style eatery where customers chowed down on Crab Rangoon (page 34), fried egg rolls, and Pineapple Fried Rice (page 151). The food my family served at work wasn’t much like the Cantonese food they cooked at home, but what they served were the product of the American melting pot, authentic in their own right. Most important, my family knew that customers found their piping-hot plates of stir-fries and noodles comforting and satisfying.

I was living in Beijing in 2007 when I started my blog, Appetite for China. In it, I recorded meals I ate around the city and interesting recipes I found in my travels around the country. I thought of the blog as a way to share with readers the everyday foods, particularly lesser-known regional specialties, eaten around China. What I didn’t expect were readers back home in the United States emailing again and again, asking for recipes for dishes they grew up eating at Chinese restaurants in their own hometowns. How do you get the perfect crunchy exterior for General Tso’s Chicken (page 70)? How do you fold a wonton? How do you make flavorful Hot and Sour Soup (page 52) without MSG? How do I get the rich red exterior on Chinese Barbecued Pork (page 97) without food coloring?

So here it is: a collection of more than eighty recipes for making your favorite restaurant Chinese foods at home. Additives such as MSG and food coloring have been eliminated, and a few vegetarian variations have been included, but otherwise the dishes are true to their tasty, saucy, nostalgia-inducing origins. Most, like Orange Chicken (page 76) and Moo Shu Pork (page 100), are takeout classics. Others, like Lobster Cantonese (page 112) and Mini Egg Tarts (page 167), have been staples of American Chinatowns for generations. And you don’t even need to live near an Asian market or own a deep fryer to make all this mouthwatering food: Most of the ingredients can be found in your local supermarkets, and a wok or heavy-bottom pot, along with a fine-mesh strainer, work well for all the frying recipes in this book. So put those takeout menus back in the drawers, roll up your sleeves, and let’s get cooking!

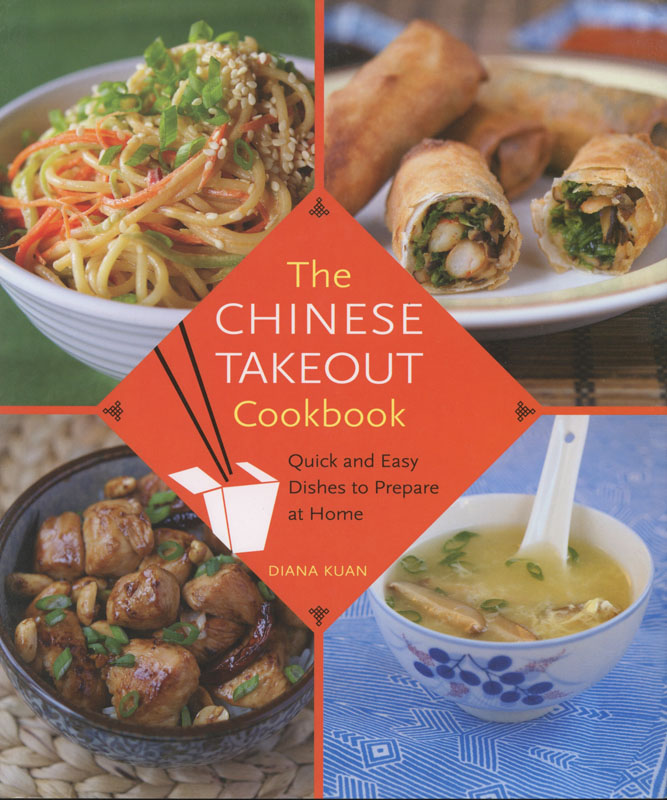

COPERTINA

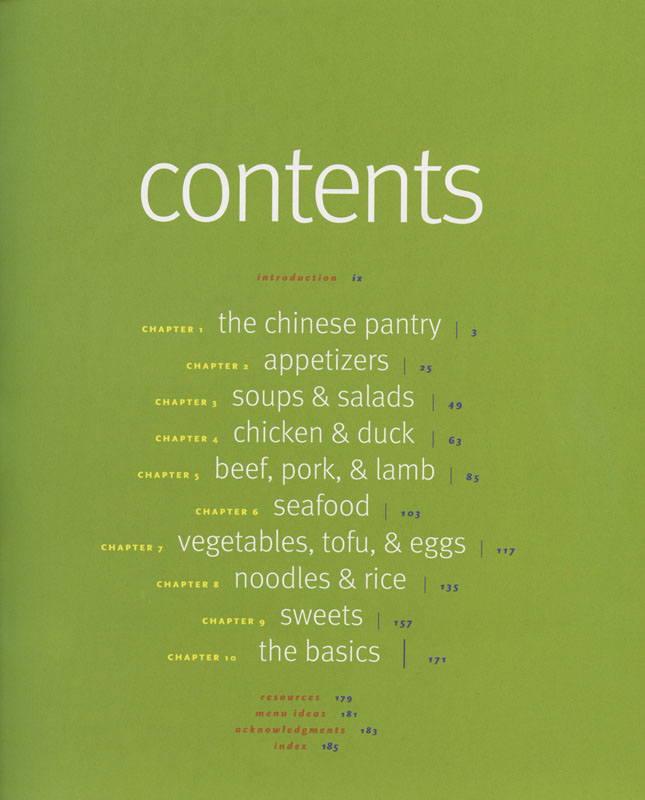

INDICE GENERALE

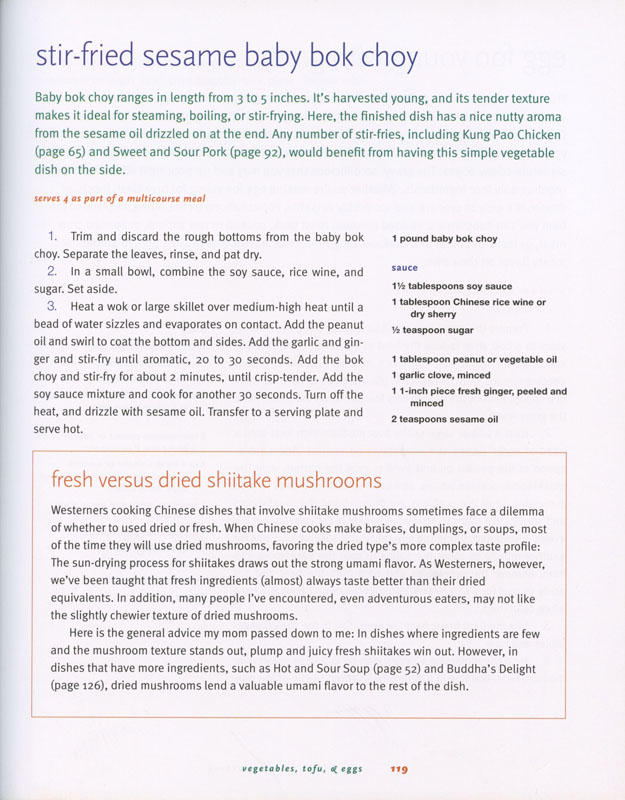

ESEMPIO DI RICETTA